Want to learn more about our day to day?

We post frequently here on our Blog, with updates about the construction, planning, and resource gathering for the space.

So what is a Food Forest, and why are we making one?

May 29th, 2024

At it's simplest, a Food Forest is a sustainable agricultural system designed to mimic a natural forest ecosystem.

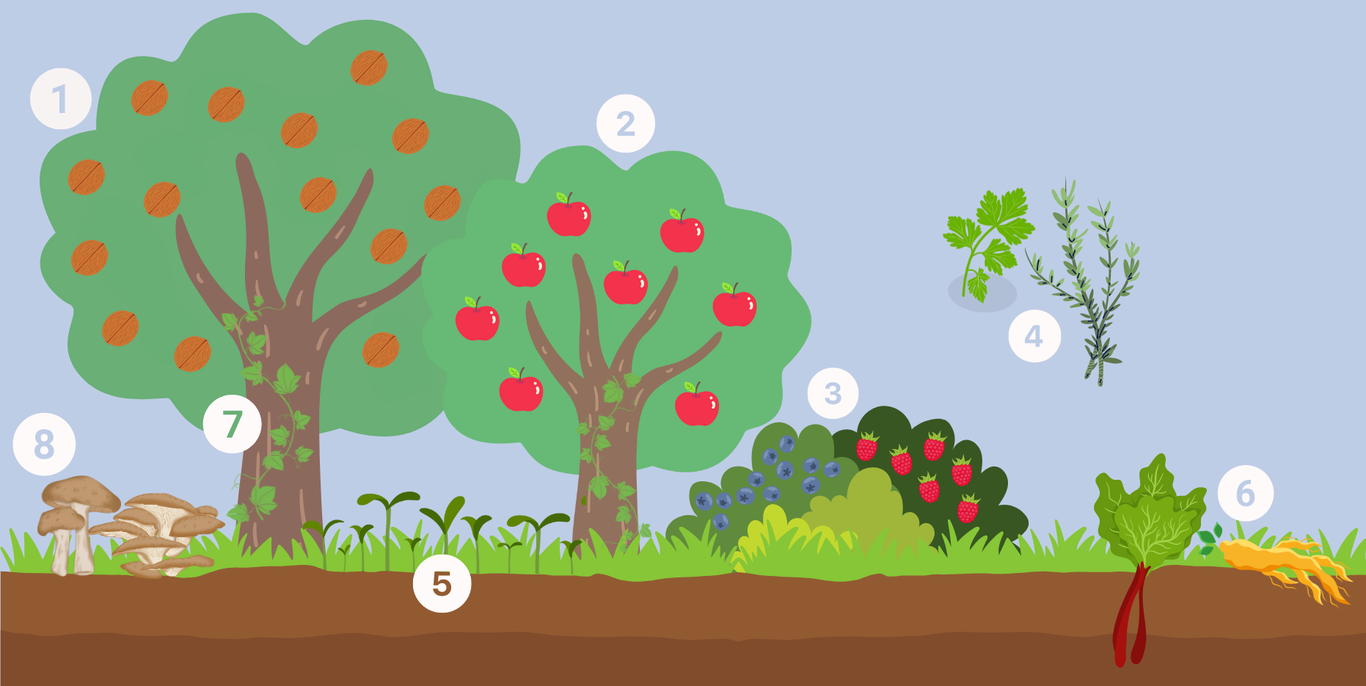

Generally, there are eight layers to a Food Forest. Each layer represents a different set of fruits, vegetables, herbs, and other edible plants. The goal of a Food Forest is to fill a space to the brim with as much biodiversity as possible, creating an ecosystem of edible and non-edible plants that can provide for humans, as well as the native wildlife. We chose to make a Food Forest because they mimic the autonomous ecosystem of a forest, they're low maintenance, improve air quality, and have a positive effect on the land surrounding them. They connect communities with nature and provide space for the plants within them to help one another grow sustainably.

Layer 1 - The Tall Tree or Canopy Layer

This layer consists of large trees that provide protection to the layers underneath it; it’s composed of trees that are typically around 9 meters (30 feet) high or more when fully mature. These trees can include large nut trees, such as walnut or chesnut, fruit trees like pears and plums, or non-food producing trees such as oak and pine. However, dense, spreading species of trees can block too much sunlight from the lower layers, so maple and pine are not great options for a canopy layer.

Layer 2 - The Sub-Canopy or Large Shrub Layer

The sub-canopy layer is commonly comprised of smaller fruit tree's such as apple, apricot, lemon, peach, or cherry trees. This layer is shorter than the first, but can be considered the top layer in residential areas where 30 ft high trees are not an option. These trees typically grow to be about 10 to 30 feet high, and are incredibly beneficial to wildlife.

Layer 3 - The Shrub Layer

This layer in the Food Forest includes flowering, fruiting, wildlife attracting shrubs. Berry bushes, such as raspberry, strawberry, and mulberry, are common, but it can also include medicinal plants such as witch hazel and elderberry. Shrubs can come in all different shapes and sizes, which makes them useful for planting in any space that needs coverage. This layer can also act as a natural barrier in more structurally developed gardens.

Layer 4 - The Herbaceous Layer

The herb layer doesn't just consist of your run of the mill herbs, it can also include any non-woody vegetation, such as vegetable and flowers. This layer consists of plants that you would typically expect to find in a backyard garden: garlic, asparagus, kale, rhubarb, basil, parsley, rosemary, cilantro, chamomile, and many more.

Layer 5 - The Ground Cover Layer

Ground cover includes low, ground-hugging plants—preferably varieties that offer food or habitat—that can fit into the edges and the spaces between shrubs and herbs. This includes clover, creeping thyme, mint, flowers such as phlox and verbena, and even strawberries.

Layer 6 - The Vine Layer

The vine layer is exactly what it sounds like. This layer is for climbing plants that can make their way up tree trunks and branches, filling all unused spaces with food and habitat. Kiwifruit, honeysuckle, passionflower, grapes, vining berries, along with melons, squash, and cucumbers can all be found in this layer.

Layer 7 - The Root Layer

The soil is one of the most important parts of a Food Forest, and we should utilize it to it's full potential. Root vegetables such as daikon, ginseng, ginger, scallions, potatoes, and leeks are perfect for this layer. Even some flowers such as dahlia and lily can grow well in this layer, and they produce starchy tubers that can be used as vegetables or ground into flour. However, deep-rooted varities of plants such as carrots don’t work well because the digging they require will disturb the other plants of the forest. The goal is to provide easily accessible, edible plants that can be harvested without disrupting the ecosystem that has been created in the area.

Layer 8 - The Mycellium Layer

This layer is not always included in the design of a Food Forest, largely because fungi are always going to be a part of any natural forest. But planting a mycelial layer can actually help plants to create a stronger root system and to grow more healthy. The mycelium network of fungi helps to transport moisture and nutrients around different areas of the forest.

Above is a depiction of some of the plants commonly found in each layer of a Food Forest. If you want to learn more about Food Forests, visit Project Food Forest by clicking the button below!

Vermiculture and Its Role in our Garden

June 24th, 2024

Vermiculture - the cultivation of annelid worms, especially for use as bait or in vermicomposting.

On June 14th, we undertook a fun and educational DIY project. With the help of Adam from Man of the Red Earth, an Arkansas vermicomposting and amended soil company, we built two large bins in which to store our favorite composting critters: worms! We had a lot of fun with this project and are looking forward to filling the bins to the brim with the slippery fellas.

A huge thank you to Adam and Man of the Red Earth for helping us out with this and letting us practice our construction skills!

So what is vermicomposting?

Vermicomposting is the process of utilizing worms to break down organic material into compost that contains worm castings (basically worm poop). These castings provide nutrients that are readily available for the plants, resulting in larger, healthier crop yields. This is an extremely beneficial and effective process, especially when cultivating a sustainable garden. Vermicompost improves soil health by increasing the amount of organic matter in the mixture, which improves aeration and texture, which in turn improves water and nutrient retention. Having worms crawling around in your crops creates a balanced ecosystem that encourages the growth of fungi and beneficial bacteria.

Vermicomposting can also reduce the need for reliance on harmful pesticides and synthetic fertilizers. It decreases the amount of pest attacks and risk of plant diseases, proving to be a much safer and more effective alternative to chemical based fertilizers. Vermicompost can recycle food trash, paper sludge, and other miscellaneous yard debris, which can help keep your garden clean and maintain a healthy recycling of matter.

What's the story with the worms?

The two main types of earthworms: Eisenia foetida and Lumbricus rubellis are the most commonly used to produce vermicompost. The worms thrive at temperatures between 55 and 77 degrees farenheit, and need a moist bedding to live in. They require in a dark environment, since their skin is photosensitive. Worms can live in harmony with most creatures, including mites, springtales, and pot worms, and if the bin is outdoors (which ours is not) lots of creatures can make their way into the bin and cohabitate with the worms, such as snails, spiders, even small lizards like salamanders and a variety of other small bugs.

What goes in the bin?

Worms are not picky by any means, they will eat food fruit, vegetables, manure, grains, coffee grounds, paper, crushed eggshells, and more. Citrus, however, is toxic to worms, so it should be avoided. Odorous foods such as garlic, onion, dairy products, and greasy foods are also best to be avoided. Chopping up the material before adding it to the bin will lead to faster decomposition by making it easier for the worms to chow down on.

What's our next step?

We have our bins, but have not yet got our worms. We're looking forward to get to that stage in our project, but we've still got lots of other parts of the garden to develop first. Below are some photos from our day of making the bins!

Credits and Resources:

CalRecycle Vermicomposting: Composting with Worms

EPA Composting at Home

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.